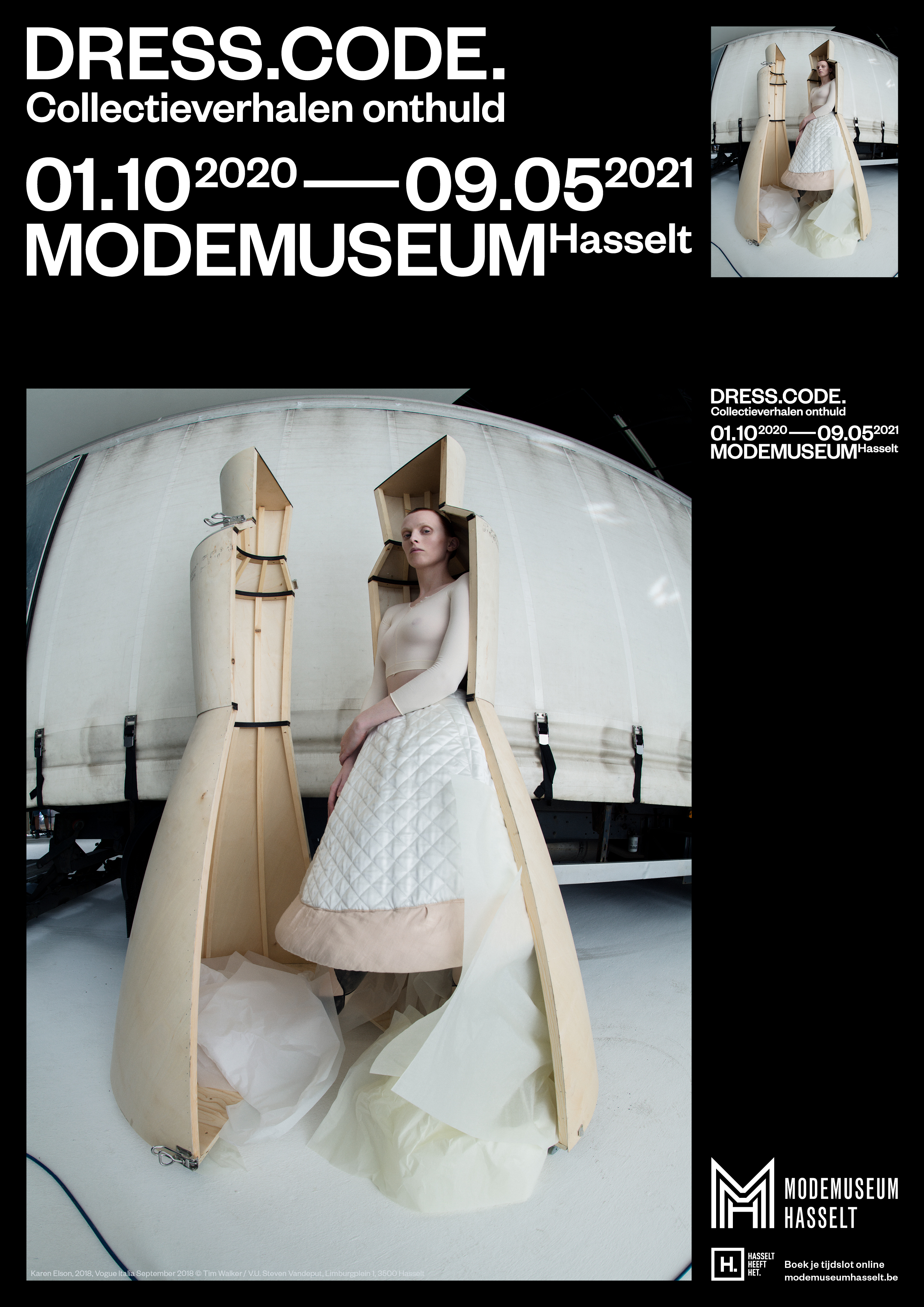

DRESS.CODE

The exihbition

We use clothing as an expression of who we are and what we stand for: from the latest fashions to bold prints, bolder haircuts, and favourite designers. Hidden beneath this conspicuously constructed reality are subconscious stories told through the clothes we wear. Knee marks on our trousers, worn soles on our shoes, a jam stain on our favourite shirt – all are tangible reminders of our intangible reality.

DRESS.CODE. applies the principles of object-oriented research. By reading and analysing form, fabric, folds, stains, and labels, we can bring inanimate objects to life and reconstruct a biography for both object and owner.

The exhibition explores the research process through various themes that serve as codes to crack the language spoken by clothing: form, fabric, vanitas, identity, and stories. Visitors are taken on a journey of discovery in search of personal and cultural stories about beauty, identity, conviction, hope, gender, and more.

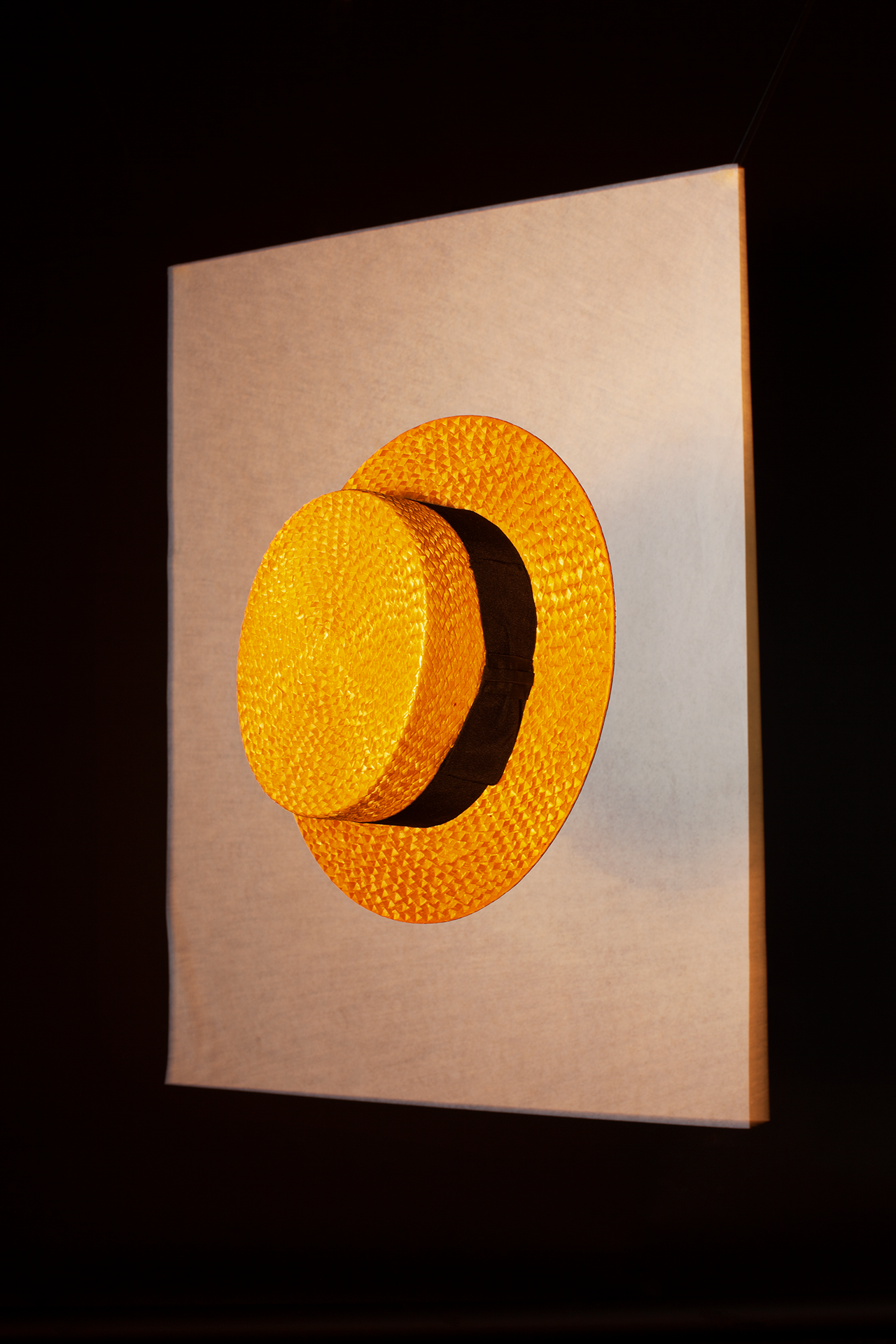

CODE I - Form

The shape of a trouser leg, the curve of a sleeve, the length of a skirt, and the height of a waist all hint at changing fashion trends and help to date an item. Fashion helps us shape who we want to be and how we want others to perceive us. ‘Body management’ plays an important role in this. Various tools were used in the past – and are still being used today – to control and curate the body. The corsets, cushions, panniers, crinolines, and bustles of yore have made way for diet and exercise in our pursuit of the ideal body as an indicator of wealth and status.

Fashion designers use their visual language to express their own beauty ideals. Consider, for example, the space a body can occupy in designs by Chanel and Rei Kawakubo versus the quasi-perfect, sylphlike silhouettes preferred by Christian Dior and Gianni Versace. Juxtaposed with these idealised shapes are the 'real bodies’ that emerge through custom-made and lovingly worn garments.

The past is a source of inspiration that designers analyse, compose, and reinterpret to create new silhouettes. Identifying these individual fragments in contemporary pieces is a complex game. Sometimes we are misled, and an object appears older than it is or comes from a different culture than we thought. A careful analysis with close attention to the use of material, technique, and form will often reveal that these pieces were inspired by romantic nostalgia.

CODE II - Fabric

Fabric, colour, decoration, cost, and availability of materials help to shed light on the period in which an item was made or worn. They also hint at the tastes, personality, and background of the wearer.

Before the widespread use of synthetic materials, such as rayon in the 1930s, most clothing was made from natural fibres like wool, silk, linen, and cotton. The way these textiles were dyed, printed, embroidered, and woven also helps to accurately date them.

Over time, materials and decorations may acquire a different status and evoke different connotations. Leopard print – now found in virtually all fashion items, from prints and embroidery to (faux) fur and leather – has been part of the fashion scene since ancient Egypt, where it was associated with feminine divinity. Once considered the height of sophistication, the print now evokes connotations ranging from sexy and elegant to trashy, classy, innovative, and mainstream. Fur was considered a status symbol for centuries but lost some of its appeal in the twentieth century when ethics started to trump fashion.

Some designers have a special preference for certain materials, designs, and fabric treatments. In this theme we reveal the story behind the artistic drawing of a 1920s Zimmerman ensemble, we explore Paco Rabanne's unconventional use of materials, and we examine the whimsical print of a Norine silhouette from the late 1930s.

Colours are ascribed various symbolic meanings. In Western (Christian) culture, white is associated with innocence, purity, and eternity, as well as concepts such as peace and faith. Due to these positive connotations, white plays a prominent role in momentous and joyous occasions, such as baptisms and weddings. Groups who historically fought for justice, such as the suffragettes in the early twentieth century, also incorporated white into their outfits. Fashion uses this well-known symbolism of innocence, honesty, and purity, but ascribes new meanings and sentimental value to it as well.

Sometimes unconventional materials are used. In times of scarcity, such as wartime, alternatives were often sought and garments were made from unexpected materials. In addition, the act of recycling can be a statement against wasteful consumerism. A good example of this is Maison Martin Margiela's Artisanal collection, which offers an idiosyncratic take on haute couture.